SVB was largely a regulatory failure

I wrote about different types of bear markets previously. The worst bear markets arise not from economics (rising interest rates) or political events (European wars), but from systemic failures like the 2008 financial crisis. When the Federal Government declared Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) worthy of the systemic failure label, I pay attention.

Banking institutions are risky, but necessary public-private partnerships. They safely store customer cash and make loans. The deposits and loans do not even have to be equal. Banks can issue more loans than they keep in hard assets. In fact, this is how most money is created. Money isn’t “printed” by the Federal Reserve. They encourage or discourage banks to loan money, thereby changing the quantity of money in the economy.

Put simply, banks make profits by lending at a higher rate than they pay in interest to depositors. When rates are low like in 2020, banks might loan at (hypothetically) 4% interest and pay 0% to depositors, earning 4% over time. But when interest rates rise, the loans are locked at 4% and depositors demand 4%, too. (This is called an asset-liability or duration mismatch.)

This mismatch can be financially devastating if a bank has inadequate reserves. If the rate rise happens quickly as it did in 2021 (see graph below), it’s even more difficult to manage. If they issue enough new loans at higher rates quickly enough, they can make it all work out.

Banks and regulators also have to manage the bank's loan portfolio. It might look good to sell a bunch of loans at high (7%) interest rates, but if you have been carelessly lending money to unworthy creditors, the loans default and you make no money. This is the 2008 Lehman Brothers bankruptcy example.

Oddly, SVB didn’t make that many loans. That’s like a grocery store that doesn’t like to sell groceries. We don’t exactly know why, but it was a terrible business strategy. Their alternative was to buy boring treasury bonds that were earning 1.8% -- even lower than loan rates. In one sense, these bonds were super safe because unlike a business loan, US Treasuries will never default. But when rates rose, SVB was even deeper in the hole than the average bank because they only had these low profit bonds. This made them very vulnerable.

There were also two large regulatory failures. The first is an arcane, yet legal, accounting technique called “held-to-maturity", which conveniently disguised the fact that SVB’s Treasury bonds were earning little interest than a higher interest-rate world. Instead of showing this in plain sight on their financial statements, it was buried in a footnote.

This footnote was first identified in January of 2023 year by a former hedge fund manager who posted on Twitter. Sixty days later, SVB came clean and acknowledged it had a $1.8 billion problem. Fortunately, and unsurprisingly, this “held-to-maturity" treatment is increasingly being replaced by the more transparent alternative “mark-to-market”, but it’s not entirely gone.

SVB might still have survived if it had some time to sort this out before depositors started fearfully withdrawing money. In 1907, JP Morgan bought himself time and prevented a bank run by having his tellers count out cash withdrawals very slowly! SVB had no such option. Banking happens a digital speed. Its depositors showed no patience. In a classic example of ”Prisoner’s Dilemma“ everyone rushed to pull their money out. SVB was dead in hours.

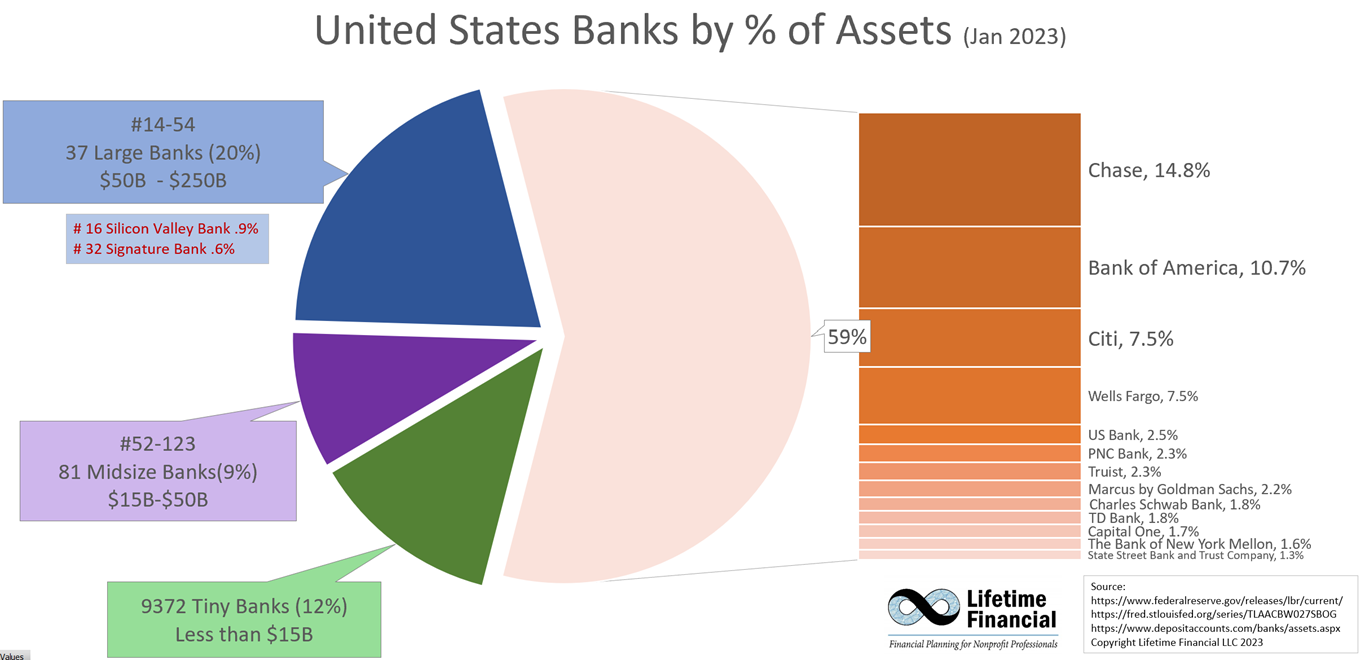

You might hear SVB and Signature being called regional or mid-sized banks as if they were small. They weren’t. As of January, they were the 16th and 32nd largest banks in the US! There are 9500 banks and credit unions in the US. Total assets of US banks are about 23 trillion dollars. More than half of those assets are in 13 banks (orange in chart below) the US calls systemic, meaning “too big to fail”. Since the 2010 Dodd Frank Act, they have been subject to much greater scrutiny.

Under the original Dodd Frank Act, SVB and similar size banks (blue in chart above) were considered systemic and were also heavily regulated. In 2018, Congress voted to rescind the Dodd Frank regulations on the blue slice, including SVB and Signature. This is one reason Republican criticism has been muted.

But in recent years bank stocks are plummeting. The Federal government is concerned this will trigger runs on other banks, so they are ensuring all SVB depositors are kept whole. It’s being called a bailout, but SVB owners, executives and stockholders are not being protected, only customer cash deposits. And now unsurprisingly, Congress is reconsidering its 2018 Dodd Frank backtrack.

Sigh. Let’s hope these events stay contained.

Every few weeks, I try to make a complex topic about financial planning or investing explainable in 750 words or less (five minutes reading time.) Naturally, this requires some simplification with which one could quibble. Reach out if you want to discuss or hear more - david@lifetimefinancial.com Also, naturally, this is not advice of any kind for any individual. It’s general material for consideration in your own thorough research.